“Now That You’ve Died”

Imagine this. You’re at a play. You don’t have to worry about getting a seat with a good view. There are no seats. There is no view. There’s a stage of sorts. You’re standing in the middle of it.

The play starts with a death. Yours.

“Now That You’ve Died” is an ingenious and powerful walk-through story-telling, written by Carnegie winner Patrick Ness, directed by Hector Harkness and Kate Hargreaves and narrated by Christopher Eccleston (Doctor Who, Song for Marion).

Our tiny audience group numbered eight in total. We were first led through a desolate-looking basement, were the disembodied voice of Mr Eccleston told us (without ceremony but with a degree of wry humour) that we were all dead. We were welcome in the afterlife, but we would have to move on quickly. Thousands more new and hungry dead would soon be piling in after us, and we were not safe from them. Like well-behaved recently-deceased, we stepped into the waiting lift, which quickly succumbed to utter darkness…

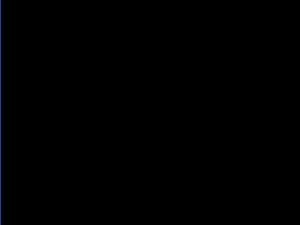

…and remained dark until the end of the play.

This was a play for every sense except sight. We were intensely focussed on the subtle and unpredictable motions of our ‘lift’, faint whiffs of smoke, the taste of our rations and of course the voice of Eccleston, talking us through our afterlife journey with a beautifully judged mixture of sympathy, cynicism, black humour and menace. We imagined things too, as our minds tried to fill the void, seeing non-existent shapes in the darkness and feeling the warmth from unreal flames.

Darkness isn’t just an inconvenience. It afflicts your mind, making you feel powerless. The narrator and his comrades were invisible to us, the only glimpses of them offered through spoken descriptions, in a chilling accumulation of detail. But the narrator made it very plain that they could see us. They could see not only what we were doing, but everything we’d ever done, felt or thought.

Darkness isolates. There were no ghost train shrieks or giggles as our strange vessel ground, glided and shook along its mysterious route. None of us could exchange glances or smirks to forge a sense of wry camraderie. We were all trapped in our own heads, forced into introspection.

When you’re stranded with only a voice for company, you can’t help giving it your full attention, and letting its words play out across the stage of your mind. How far will you let that all-powerful voice lead you, as it tells you to cast aside everything that belongs to your old life – memory, regret, guilt and love? And at what point, in the quiet of your own head, do you start to rebel?

Despite the ominous theme, the final effect of the play was actually very uplifting. It was a story about resilience in darkness, about what is kept when all is lost, about what is important and what is not.

After a temporary darkness had affected me so powerfully, it was humbling to be reminded that a very large number of people handle loss of vision on a daily basis. In fact, this was the point of the event. The performance had been arranged by the RNIB to raise awareness of Read for RNIB Day on 11th October.

For the curious, here’s a behind the scenes video about “Now That You’ve Died”, including an interview with Christopher Eccleston.